The noun, “dead” (νεκρὸς), when used figuratively in New Testament literature, has a relational sense when used of people, and an effectual sense when referring to other realities such as sin, the law, and faith. Its consistent use indicates something’s ineffectualness, or inability to influence or act upon someone, rather than non-existence. Recognizing this pattern of use, and resulting sense, should help in the debate over the meaning of “dead faith” in James.

Introduction

The noun, “dead” (νεκρὸς) occurs 127 times in the New Testament, with at least 20 occurrences being figurative.[1] Its verb form occurs three times, once in a figurative sense.[2] What is the basic sense of this figurative use? Is there a consistent nuance to its use, or does it carry a diversity of significances? For example, does it indicate non-existence, past existence, inability, a combination of senses, or something else? These questions shall be explored by examining the various instances where it is used figuratively.

People with Respect to People

Twice in the New Testament νεκρὸς is used to describe people who are alive, but somehow cut off from communion with loved ones. In one instance physical death separates the two. In the other instance, distance separates the two.

DEAD MEN BURY DEAD MEN (MATTHEW 8:22 AND LUKE 9:60)

The first figurative use of “dead” is found with Jesus in the Gospels. In these two parallel passages Jesus addresses a young man whom He calls to follow Him, but who then seeks to delay joining Jesus in order to “bury” his father. His father most likely was either dying or had died earlier. He would not have died that day. The practice of that time was to bury someone on the day of their death. The young man would have been at home with the family, not out in public if that were the case. If his father was dying, then the delay would be for an unspecified time. At any rate, a son’s recognized duty was to care for his father in these circumstances, and so his request might not seem unusual or unreasonable. On the other hand, as noted by Craig Keener, “One of an eldest son’s most basic responsibilities (in both Greek and Jewish cultures) was his father’s burial. The initial burial took place shortly after a person’s decease, however, and family members would not be outside talking with rabbis during the reclusive mourning period immediately following the death. It has recently been shown that what is in view here instead is the secondary burial: a year after the first burial, after the flesh had rotted off the bones, the son would return to rebury the bones in a special box (an ossuary) in a slot in the tomb’s wall. The son in this narrative could thus be asking for as much as a year’s delay.”[3] This gives us better insight into Jesus’ response.

When Jesus says, “Let the dead bury their own dead,” Bullinger identifies this figure as antanaclasis (word-clashing) in which the same word is repeated in the same sentence, but with a different meaning.[4] The first use of dead may also be viewed as either a metaphor or metonymy.[5] That Jesus is speaking figuratively is evident, though, because someone must be alive to bury a dead person. Thus His first use of “dead” refers to living people who are quite active, though His second clearly should be taken literally. The common interpretation of this passage is to see Jesus referring to those left behind by the disciple as “spiritually dead.”[6] They are either not following, or not being called to follow Jesus. Though this is an “evangelistic” interpretation of Jesus’ words, nothing in the context requires this meaning beyond His reference to preaching the coming kingdom in Luke’s Gospel. Willoughby Allen raises the possibility that this may be a proverbial saying carrying the sense of “cut yourself adrift from the past when matters of present interest call for our whole attention.”[7] This would then follow the idea expressed by D. A. Carson, that these words are a “powerful way of expressing the thought” that “even closest family ties must not be set above allegiance to Jesus and the proclamation of the kingdom.”[8] Alternately, Jesus may be referring to those elderly who are awaiting their own deaths and would be unwilling, or unable, to follow Him. The “dead” doing the burial are not inactive, nor are they corpses, but are viewed as dead in some non-literal sense.

SEPARATED FROM LOVED ONES (LUKE 15:24, 32)

The prodigal son is another example of a living person being called “dead.” The term is used by the father to describe the significance of their separation. His son passes from the “dead” status to “living” with his return to the presence, and therefore fellowship, of his father from whom he had separated himself. His deadness is described from the perspective of the father, not the son. And, again, in his deadness he is very active, though not acting as a son should. Robert Stein correctly identifies the metaphor, but misunderstands its significance when he makes the father’s description of his son as “dead” to mean “spiritually dead” and “alive” to mean “saved,” or, “possessing life in God’s kingdom.”[9] Nothing in the text requires or implies such a meaning. Jesus’ point in the three parables (lost sheep, lost coin, lost son) is our response toward the repentant, not who is regenerate (saved) and who is not, or how to become regenerate.[10] I. Howard Marshall notes the Jewish background by which “dead” could carry the sense of having been disinherited and was now returned to the family, though he does not endorse it. Rather he sees the son “as good as dead.”[11] John Noland understands the significance of the terms better when he notes that “the father does not use the language primarily in connection with the son’s experiences in the distant land—he does not know about this except by supposition, and minimally from the state in which he finds his son—but in connection with his own “bereavement” and “finding again” of his son: the language is relational.”[12] Further, the point of all three parables is crystallized in the contrast between the father’s response, representative of God the Father, and the eldest son’s, representative of the murmuring Pharisees. But, here again, “dead” does not mean non-existent or that he was lying around as a corpse. Rather, it vividly pictures the pain and sorrow caused by separation and inability to commune with a loved one.

People with Respect to Things

A second figurative use of νεκρὸςdescribes living people’s relationship to conceptual or non-living things. In this case, these entities have no influence on the person and so are “dead” in relation to them. These include both sin and the Law.

DEAD TO SIN (ROMANS 6:11, 13)

Paul uses the imagery of death contrasted with life to describe the believer’s attitude toward and response to sin and God. His metaphorical use of “dead” in Romans 6 anticipates the imagery of the following chapter wherein the literal death of a husband frees a woman from the law of marriage. Here he does not describe sin as dead, but says that believers are to view themselves as dead to it.[13] This relationship to sin is a result of our identification with Christ who died literally and lives literally.[14] Kenneth Daughters notes well that “these verses make it clear that sin has not died, but rather we have died to it. And furthermore, the issue at hand is sin’s mastery. … Just as Christ died once for all, never to die again, so we have permanently been liberated from sin’s mastery. And just as Christ now lives His life to God, so we should follow in His steps.’[15] We can do this because sin no longer has the power to make us sin, we are “dead to its power” and “ought to recognize that fact and not continue in sin.”[16] Carson clarifies our relationship to sin in this context. “To be ‘dead to sin’, thus, does not mean to be insensible to its enticements, for Paul makes clear that sin remains for the Christian an attraction to be battled with every day (see v 13). Rather it means to be delivered from the absolute tyranny of sin, from the state in which sin holds unchallenged sway, the state in which we all lived before conversion (see 3:9). As a result of this death to sin, we can no longer live in it (2b)—for habitual sinning reveals sin’s tyranny, a tyranny from which the believer has been freed.”[17] James Dunn agrees. “The figurative sense is well enough known … and so would be sufficiently meaningful and realistic—‘dead’ in the sense of ‘lost to,’ ‘completely out of touch with’; … The death is not an actual death, nor a mere playing with words, but a living in relation to the power of sin (see on 3:9) as to all intents and purposes dead.”[18] Again, this use of “dead” does not mean people are inactive or cease to exist with regard to sin. Rather, they are not impacted by it. It is ineffective in influencing or controlling them.

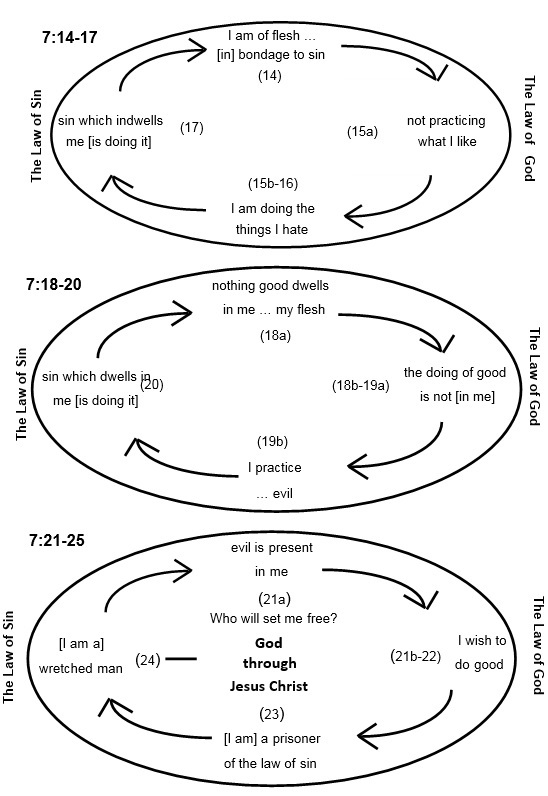

DEAD TO THE LAW (ROMANS 7:4, 6)

Not only does Paul describe our changed relationship to sin as “dead,” but also our changed relationship to the Law.[19] Using the imagery of a once-married widow’s relationship to her departed husband, Paul describes “the believer’s transfer from the domain of the law to the domain of Christ.”[20] He teaches that the Law no longer has jurisdiction over a believer because of his or her identification with Christ. Paul’s sense is that the believer “is no longer enslaved to the law.”[21] John Witmer sees the connection between this use and what Paul said in Romans 6 about the believer’s relationship to sin. And, in fact, the two concepts are parallel, with Paul using the same metaphor to describe the believer’s relationship to the Law as identical to that of his relationship to sin. “Just as a believer ‘died to sin’ (6:2) and so is ‘set free from sin’ (6:18, 22), so he also died to the Law and is separated and set free from it.”[22] William Mounce notes that this “death of the believer took place when by faith that person became identified with the crucified Christ” whose death was very literal, but also changed Jesus’ relationship to the Law as well.[23] Again, in this imagery the Law is still very much alive and present, and the Saint is very much alive and active. But, any relationship they once shared is severed. And, in this case, the Law loses its ability to command obedience or bring condemnation.

People with Respect to God

A third figurative use of νεκρὸςis to describe living people’s relationship to God. This is a relationship of separation rather than non-existence on the part of the person. Further, the “dead with respect to God” person is still very present and active in the expression of his or her deadness.

DEAD ELECT (EPHESIANS 2:1, 5)

Ephesians 2 introduces us to a fascinating insight into the life history of every elect person.[24] When writing the Ephesian Christians, Paul uses a synecdoche (effect for the cause) to describe those chosen “before the foundation of the world” (1:4) as being “dead” before the day they become saints by spiritual birth. This state of deadness is not a state of inactivity, but a lifestyle.

Prior to their conversions, Paul’s readers were very active, but their conduct was not in the sphere of good works (2:10) to which they were subsequently spiritually born. In this state of death, the elect were identified with “the sons of disobedience” who are “children of wrath” (2:2-3) rather than being “blessed with every spiritual blessing” (1:3) including communion with God.

The elect person, who has not yet believed and therefore been regenerated by the Holy Spirit, is described by Paul as “dead.”[25] This cannot mean non-existent or unable to act, but unable to respond positively to God.[26]So, “dead” does not mean a lifeless corpse,[27] but a separated pre-saint, someone unable to commune with or respond to God.[28] Kenneth Wuest describes it well. “Death itself is a separation, whether physical, the separation of the person from his body, or spiritual, the separation of the person from God.”[29]

Ephesians 4:17-19 describes the “dead” life of Gentiles, the sons of disobedience. Again, it is not inactivity, but activities apart from God that Paul lists. He moves from this description to contrast the “old man” (4:22-23) with the “new man” (4:24). Both are active, but their conduct is very different, depending on whether they are “dead” or “alive” to God. These verses explain what Paul means in Colossians 2:13. “This I say, therefore, and testify in the Lord, that you should no longer walk as the rest of the Gentiles walk, in the futility of their mind, having their understanding darkened, being alienated from the life of God, because of the ignorance that is in them, because of the blindness of their heart.” They are living, active people, separated from the living God and unable to commune with Him.[30] That being said, as the elect, they are not destined for destruction, but salvation. Even so, their pre-justified state is the same as that of the non-elect which is a life characterized by death as expressed in their deeds.[31] Harold Hoehner describes: “This death is spiritual, not physical, for unsaved people are very much alive physically. Death signifies absence of communication with the living. One who is dead spiritually has no communication with God; he is separated from God. The phrase ‘in your transgressions and sins’ shows the sphere of the death, suggesting that sin has killed people … and they remain in that spiritually dead state. … Both suggest deliberate acts against God and His righteousness and thus failure to live as one should. The plural of these two nouns signifies people’s repetitious involvement in sin and hence their state of unregeneration.”[32]

PRE-CONVERSION ELECT ARE DEAD SLEEPERS (EPHESIANS 5:14)

Later in Ephesians, Paul again uses the imagery of death to conclude a call to a changed lifestyle with a poetic interlude. This short poem may be an allusion to or paraphrase of Isaiah 60:1.[33] Or it may be a quote from an early church hymn.[34] At any rate, it is the culmination of a call to be different from the world out of which his readers had been saved. It is interpreted in one of three ways.

First, the sense of “dead” in this poem is thought by some to refer to the readers’ previous identification with the unregenerate.[35] Thus it is a call to the unregenerate to come to Christ for salvation.[36] “Arise” then alludes to their identification with Christ’s resurrection.[37] A second view sees it as addressing both believers and unbelievers. “Believers are called on to ‘awake’ out of sleep; unbelievers, to ‘arise’ from the dead.”[38] A third approach takes it as addressing only the church. It is a call “not to life still, as if she were asleep or dead,” but to be a light to the world; “not to sleep or loiter, but spring forth as if from the grave, and pour light on the world.”[39]

Since the context of the passage is the Christian’s separation from a sinful mindset and lifestyle, described as darkness, this passage metaphorically applies the previously stated truth that dark deeds are exposed by the light. Since believers are not to be a part of that dark world, the call is best seen as addressing the church. “You who sleep” and “the dead” are synonymous terms. “Light,” then, must allude to life. So, if this were a resurrection formula, “the dead” could be taken literally. But, in the context of the Ephesian church and its possible allusion to Isaiah, it is better to see “the dead” as symbolic of those formerly spiritually dead upon whom Christ “shines” as their Savior. Thus, these “dead” are physically living, previously unregenerate people, who had been separated spiritually from God until Christ changed their status. This call is a reminder to the Ephesians of their previous call out of darkness to become light in the Lord (verse 1).

DEAD IN TRESPASSES (COLLOSIANS 2:13)

In Colossians 2:13 Paul is addressing his readers’ identification with Christ in their salvation. In the process, he describes them as previously “being dead” in trespasses and “the uncircumcision of your flesh.” This use of “dead” again refers to their spiritual condition, not physical.[40] And so death here is a metaphor for separation from God which ultimately means lacking the life of God. [41] MacDonald and Farstad conclude “This means that because of their sins, they were spiritually dead toward God. It does not mean that their spirits were dead, but simply that there was no motion in their spirits toward God and there was nothing they could do to win God’s favor.”[42] Richard Melick notes, “In these equations, ‘dead’ and ‘uncircumcision’ form a semantic field so that they refer to the same condition. They both confirm the fact that believers’ circumcision occurs at salvation and reaffirm that the ‘unhandmade circumcision’ corresponds to being made alive.”[43] James Dunn relates the terms more to the Jewish background of the Colossian heresy. “Their ‘being dead’ refers to their status outside the covenant made by God with Israel (cf. again Eph. 2:12). That is to say, their ‘transgressions’ (παραπτώματα, usually violations of God’s commands) would be those referred to already in a similar passage (1:21), the transgressions of the law that from a Jewish perspective were typical of lawless Gentiles (see on 1:21). The Jewish perspective is put beyond question with the complementary phrase ‘you being dead (“although you were dead”) in … the uncircumcision of your flesh.’”[44] So, they were separated from God, not inactive. They, as elect, could not commune with God while in their spiritually uncircumcised state.

A State of Being

A fourth figurative use of νεκρὸςinvolves describing regenerate people, thus who are spiritually “dead,” with regard to their being out of fellowship with God. This use is not a denial of their salvation, but a description of the seriousness of their condition.

DEAD BODIES WITH LIVE SPIRITS (ROMANS 8:10)

Having addressed the issue of the sin nature, Paul turns to the Spirit’s work in the believer’s life. Robert Hughes and Carl Laney note that “these verses expand and elucidate the contrast between the mind conditioned on and patterned after the flesh and the mind conditioned on and patterned after the Spirit.”[45] The believer’s body is “dead because of sin.” This metaphorical use of “dead” clearly does not mean presently, literally, dead. But in what sense is the believer’s body dead?

The first view sees “dead,” as used here, describing the regenerate person’s continued physical mortality. In this passage the believer’s body and spirit are distinguished in their experience.[46] While the body is still subject to the consequences of sin, and will die physically,[47] the believer’s spirit is immune to its power.[48] As a result, the believer enjoys the life of God now and anticipates resurrection.[49] This is accomplished by the Holy Spirit who supplies “the risen life of the Lord Jesus” in the life of the believer.[50]

A second view proposes that Paul is describing the inner man rather than the physical man. Charles Pfeiffer and Everett Harrison represent this approach. “The false self is dead or useless because of sin. This self cannot be effective for God. But the spirit—the true self—is living because of the righteousness which God bestows. Of course, there are not two separate selves. When the self becomes false, it acts in accordance with the flesh. When the self is true, it acts in accordance with the Spirit.”[51] However, since Paul calls the body dead, and not the man, the former view is best. He uses “dead” to refer to mortality and anticipates resurrection with the promise of life.

DEAD WIDOWS (1 TIMOTHY 5:5-6)

Paul, in giving instructions to Timothy about the support of widows, warns him not to support some. In particular those that give themselves over to wanton pleasure were to be excluded. He uses oxymoron[52] to describe them as being “dead” even while they “live.” This use of “dead” is almost universally understood to be a figurative way of saying she is not spiritually right with God. Some see this as describing a believer whose life has become spiritually empty.[53] The majority question her salvation and see Paul saying she is spiritually dead while physically alive, “a mere professor” and, by implication, unregenerate.[54]A third option is to see “dead” referring to her as “useless to God and others,” but still a believer.[55]

This “dead” person is certainly active, but not doing what pleases God. Her activity is sinful. She is not a corpse, but quite alive. Yet, she is certainly not devoting herself to prayer, and thus is not experiencing communion with God.

A DEAD CHURCH (REVELATION 3:1)

The last figurative use of “dead” in the New Testament is found in Revelation 3:1 with Christ’s criticism of the church at Sardis. He calls the church dead and warns them to salvage what they have left of their life. But what does Jesus mean by a “dead” church? This use of dead indicates a lack of life in the church with a reputation for being alive.[56]

One approach is to see “dead” in this context still to mean the church is basically unregenerate, either because many of its members had “forfeited” their salvation,[57] or because the church congregation was mostly composed of unregenerate members.[58] Charles Feinberg describes it as “full of empty profession” because “the union of church and state brought about more profession than life.”[59]

A second approach is to see the church as a whole, rather than its individual members, as spiritually dead.[60] This is better since the promise of heavenly rewards to those who overcome in all seven churches is based on their deeds rather than as a gift of God’s grace for their faith. Further, the danger of a removed lamp stand is addressed to each church as a whole rather than its individual members. G. K. Beale understands well Jesus’ use of figurative language here. “Though it considered itself spiritually alive, and perhaps other churches in the region respected the Sardian Christians, in reality, they were in a condition of spiritual death (cf. other such uses of ‘dead’ in the NT). Verse 2 reveals that this assessment of their condition is a figurative overstatement (hyperbole) intended to emphasize the church’s precarious spiritual state and the imminent danger of its genuine death.”[61] If they did not “get their act together” spiritually, the church would cease to exist when Jesus removed their lamp stand. David Aune sees Jesus intending a paradox using the contrasting metaphors of “life” and “death” to “represent moral and spiritual vitality and morbidity.”[62]

Again, though called dead, the church’s members were living human beings and the church was active, though not in a spiritually vital way.

Inanimate Concepts

A fifth use of νεκρὸςinvolves concepts rather than human beings. These are realities affecting humans and can be described in terms of their influence on humans. Recognizing their figurative sense and the intent behind its figurative use should also shed light on the interpretation of these difficult passages.

SIN IS “DEAD” APART FROM THE LAW (ROMANS 7:8)

As he continues his discussion of the believer’s relationship to the Law and sin, Paul personifies sin and employs the same metaphor to describe it as being “dead” apart from the Law. Then, in detailing its impact, he describes himself as starting out alive and ending up dead when personified sin uses the Law to produce evil desires in him. But what does he mean by sin being “dead”? The two major interpretations are that sin is nonexistent,[63] or that it is dormant or inactive.[64]

In this description of the believer’s struggle with his sin nature, sin is neither absent nor inactive, even when “dead” apart from the Law. It is just unable to act upon its intended victim.[65] If it were absent or non-existent, it would not be able to “take the opportunity” when the Law came in. As Paul describes it, sin is essentially standing by until it finds a means of killing him, namely, the Law. Dunn describes it as “ineffective” and “powerless.” William MacDonald and Art Farstad see a slightly different nuance. “The sinful nature is like a sleeping dog. When the law comes and says ‘Don’t,’ the dog wakes up and goes on a rampage, doing excessively whatever is forbidden.”[66] Though inactive, when the Law comes, sin uses the commandment to “deceive” and “kill.” Thus Paul’s use of “dead” to describe sin does not indicate its non-existence or even its inactivity, but only its inability to influence and act on him. Sin, now active, “produces” death in Paul in verse 13. But this death also is not inactivity or non-existence, but a condition of existence that is a consequence of disobedience. In this context it is not hell, but loss of communion with God, separation from fellowship with God in the life of a believer.[67] Paul does not lose his salvation. He just loses his enjoyment of the benefits of that salvation, his experience of eternal life in this life.

WORKS ARE DEAD APART FROM FAITH (HEBREWS 6:1; 9:13-14)

Twice the author of Hebrews uses the terms, “dead works,” a metonymy of effect,[68] as a contrast to serving God. The contrast does not imply the absence of works. On the contrary, there are works being done, but they are ineffective in pleasing God. Further, the contrast assumes the existence of those works, though they are the wrong kind. But what does he mean by this?

First, this could refer to works “devoid of faith.”[69] This is argued on the basis that “dead works” is paired with and thus contrasted to “faith toward God.”[70] Thus, they might not be sinful acts, but “works without the element of life which comes through faith in the living God.”[71] They are works done by the unregenerate “in an effort to earn their own cleansing.”[72]

Second, this may be works which were good under the Law, but “now are dead since Christ has come. For example, all the services connected with temple worship are outmoded by the finished work of Christ.”[73] For Jewish converts to Christianity, the rituals were replaced by Christ”[74] These rituals, “in contrast with the work of Christ, can never impart spiritual life.”[75]

Third, this could be works that lead to or cause spiritual death, sinful deeds.[76] For example, Paul Ellingworth argues, “νεκρὰἔργα is an expression peculiar to Hebrews … The contrast, here as in Gal. 5:19, 21, is between actions which incur the punishment of death, and the καλὰἔργα (10:24; cf. 13:21) which enable God’s people to take possession of what God has promised them (cf. Heb. 6:12). The author may have in mind the choice set before Israel by Moses in Dt. 30:15, 18.”[77] And with Eugene Nida he says, “The implication is that the useless rituals (or literally ‘dead works’) actually make the conscience unclean or impure, or even cause death.”[78]

The term “dead works” in this case, regardless of which interpretation one follows, refers to something that exists. It involves activity, but does not please God. Again, it is a relational term. The works exist, but are of the wrong kind.

DEAD FAITH (JAMES 2:17, 26)

This is probably the most disputed passage that uses the analogy of death to describe something. Using hypallage, or interchange, James tells us that faith without works is “dead.”[79] But what does he mean by that and what significance does it have in the life of a believer?

The first approach to this passage is to see James asserting that the absence of works means the complete absence of faith. For James, dead faith means “no faith,”[80] or only a false “claim to faith.” [81] MacDonald and Farstad state the view well. “What James is emphasizing is that we are not saved by a faith of words only but by that kind of faith which results in a life of good works. In other words, works are not the root of salvation but the fruit; they are not the cause but the effect.”[82] The basic logic of this position is that justifying faith continues to express itself permanently and so necessarily produces works.[83] John MacArthur states it this way. “Workless faith is dead faith, and dead faith is no faith at all. Real faith cannot die, but if you have a so-called faith that is devoid of works, it is not living faith, and it cannot save.”[84] As John Calvin is reputed to say, “We are saved by faith alone, but not by a faith that is alone.”[85] Therefore, the absence of works means the absence of faith. And, since James describes non-work producing faith as dead, it must necessarily not be justifying faith.[86] John Hart answers well the problem of calling this a false claim to faith. He notes the syntactical parallel with Romans 7:8b (“For apart from the law sin is dead”) and says, “No one would suppose that Paul intended to say that apart from the law sin was ‘false sin’ or an unreal sinfulness. Sin is still real and true sin, even apart from the law. The thought is that sin lies dormant and unrecognized until the law arouses it to action. In the same way, faith apart from works is true and real faith. But works have a way of enlivening faith and arousing it from abeyance.”[87] Furthermore, James is talking about works done to another “brother,” a fellow believer. [88]

A second view is to see faith as ineffectual, though present.[89] Keener seems to express this view and notes that “writers like Epictetus could use ‘dead’ the same way as here; this is a graphic way of saying ‘useless’.”[90] Zane Hodges argues that dead should be understood in this context to mean “sterile, ineffectual, or unproductive.”[91] Donald Burdick sees the faith as present, but not able to “save.”[92] Hart catches well the point of the analogy, that “when a Christian engages in practical deeds to benefit others, James says our faith comes alive.”[93] Kevin Butcher notes further that James, rather than defining faith, “defines the condition of a faith that is not accompanied by works.”[94]

In verse 22, faith uses works to express itself and to bring itself to completeness (perfection). James uses the analogy of the body to describe the relationship of faith to works. The body without the spirit is dead. Faith without works is dead in the same way. However, both are still there! Neither can function without the other, but both are still present. The idea here is the need for expression and activity, not a lack of existence. Further, nothing in James or any other New Testament author indicates two kinds of faith, saving and non-saving faith.[95] It is not the quality of one’s faith that saves him. Faith’s validity is in its object, God, not its source, man.

Conclusion

The use of “dead” in a figurative manner throughout the New Testament involves two major concepts. “Dead” is used relationally to describe a person’s separation from God, or from the spiritual life of God. It is also used to describe inability to act on someone or something. But, always that which is ineffectual is always present, not absent.

In most instances the figure of speech is obvious and its significance in the argument of either Jesus or a New Testament author is fairly obvious, but not always. Further, theology seems to control most people’s interpretation of the term more than the implications of the surrounding context, especially in James 2. There the general consensus is that “dead” means missing, non-existent. The absence of works means “no faith.” Yet, it is better to see it as meaning ineffectual in the same way that sin is unable to act, or get the Saint to misbehave, apart from the Law. Rather than say that the faith that justifies necessarily sanctifies, it would be better to say that the faith that justifies will not sanctify unless it continues to express itself in the life of the believer. Such an understanding allows James 2 to be a positive motivation to personal evaluation and action rather than a source of doubt in an immature believer’s life.

[1] Figurative uses include Matt 8:22; Luke 9:60; 15:24, 32; Rom 6:11, 13; 7:8; 8:10; Eph 2:1, 5; 5:14; Col 2:13; Heb 6:1; 9:14; James 2:17, 26; Rev 3:1.

[2] Rom 4:19, Col 3:5 (figurative sense), and Heb 11:12.

[3] Craig S. Keener and InterVarsity, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, Mt 8:21 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1993).

[4] E. W. Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1968 reprint), 286.

[5] It would be seen as a metaphor if the first use of “dead” is seen to describe a spiritual state of being rather than physical. It might be seen as a metonymy if “dead” is seen to refer to those about to die, the elderly of the community.

[6] Louis A. Barbieri, Jr., “Matthew” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures, 2:38 (Wheaton: Victor, 1983-c1985); Craig Blomberg, vol. 22, Matthew, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary, 148 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001, c1992); Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, 290; D. A. Carson, New Bible Commentary : 21st Century Edition, Rev. ed. of: The New Bible Commentary. 3rd ed. / edited by D. Guthrie, J.A. Motyer, 1970., 4th ed., Mt 8:18 (Leicester, England; Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity, 1994); David E. Garland, Reading Matthew (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2001) 99; Donald A. Hagner, vol. 33A, Matthew 1-13, Word Biblical Commentary, 218 (Dallas: Word, 2002); R. C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Matthew’s Gospel (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1943), 343; Homer A. Kent, “Matthew” in The Wycliffe Bible Commentary: New Testament, Charles F. Pfeiffer and Everett F. Harrison, editors, Mt 8:18 (Chicago: Moody, 1962); Leon Morris, The Gospel According to Matthew, The Pillar New Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 203; John Noland, The Gospel of Matthew, The New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 368; A.T. Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament, Vol. V c1932, Vol.VI c1933 by Sunday School Board of the Southern Baptist Convention., Mt 8:22 (Oak Harbor: Logos, 1997).

[7] Willoughby C. Allen, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to S. Matthew, Third ed., The International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, n.d.), 82.

[8] Carson, “Matthew” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 8 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1984), 209.

[9] Robert H. Stein, Luke, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary, Vol. 24 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001, c1992), 407. Also, Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Luke’s Gospel (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1946), 817. Walter L. Liefeld (“Matthew” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 8 [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1984], 984) notes this as the possible significance of the terms, but by connecting it to the language of Ephesians 2:1-5. The two passages should not be connected, nor should Paul be used to interpret Jesus in this instance.

[10] Contra John MacArthur (The Gospel According to Jesus [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1988], 153). He says, “Here is a perfect illustration of the nature of saving faith. Observe the young man’s unqualified compliance, his absolute humility, and his unequivocal willingness to do whatever his father asked of him. … His demeanor was one of unconditional surrender, a complete resignation of self and absolute submission to his father. That is the essence of saving faith.”

[11] I. Howard Marshall, Commentary on Luke, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1978), 611.

[12] John Nolland, Word Biblical Commentary: Luke 9:21-18:34, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 35B (Dallas: Word, 2002), 786.

[13] Roy L. Aldrich, “Grace in the Book of Romans, Part 1,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 97:386 (April 1940; 2002), 227; Lewis Sperry Chafer, “Soteriology,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 103:412 (October 1946; 2002) 398; Frederic L. Godet, Commentary on Romans, Kregel Classic Commentary Series (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1977), 249; W. H. Griffith Thomas, St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962), 169.

[14] John Murray, The Epistle to the Romans, The New International Commentary on the New Testament, single volume edition (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1959, 1965, 1968), 225-26.

[15] Kenneth A. Daughters, “How to Win Over Sin: An Exposition of Romans 6,” Emmaus Journal, 1:2 (Summer 1992; 2002) 119.

[16] John A. Witmer, “Romans” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (Wheaton: Victor, 1983-c1985) 2:463.

[17] Carson, New Bible Commentary, Rom 6:1.

[18] James D. G. Dunn, Word Biblical Commentary: Romans 1-8, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 38A (Dallas: Word, 2002), 324.

[19] Murray, The Epistle to the Romans, 242-43.

[20] Carson, New Bible Commentary, Ro 7:1.

[21] Brice L. Martin, “Paul on Christ and the Law,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 26:3 (September 1983; 2002) 275.

[22] Witmer, “Romans,” 465.

[23] Robert H. Mounce, Romans, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary, Vol. 27 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001, c1995), 161.

[24] Skevington Wood (A. Skevington Wood, “Ephesians” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 11 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978), 33) does not see this expression as figurative, but that a literal sense lies behind it. It is describing a spiritual reality.

[25] Most would take this to refer to spiritual death rather than physical. Examples: T. K. Abbott, The Epistles to the Ephesians and the Colossians, The International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, n.d.), 2:39; F. F. Bruce, The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984), 280.

[26] W. G. Blaikie, The Pulpit Commentary: Ephesians, ed. H. D. M. Spence-Jones, 61 (Bellingham: Logos, 2004); MacArthur, The Gospel According to Jesus, 92; Kenneth S. Wuest, Wuest’s Word Studies from the Greek New Testament: For the English Reader, Eph 2:1 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997, c1984).

[27] Contra Joel R. Beeke, “Does Assurance Belong to the Essence of Faith? Calvin and the Calvinists,” Master’s Seminary Journal, 5:1 (Spring 1994; 2002) 64; and Wiersbe (Warren W. Wiersbe, The Bible Exposition Commentary, “An exposition of the New Testament comprising the entire ‘BE’ series”–Jkt., Eph 2:1 [Wheaton: Victor, 1996, c1989]).

[28] Aldrich, “The Gift of God,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 122:487 (July 1965; 2002) 248; George Meisinger, “Salvation by Faith Alone, Part 2 of 2,” Chafer Theological Seminary Journal, 5:3 (July 1999; 2002) 23; Alfred Martin, The Wycliffe Bible Commentary: New Testament, Eph 2:2, Charles F. Pfeiffer and Everett Falconer Harrison editors (Chicago: Moody, 1962).

[29] Wuest, Wuest’s Word Studies from the Greek New Testament, Eph 2:1.

[30] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Eph 2:1.

[31] Carson, New Bible Commentary, Eph 2:1.

[32] Harold W. Hoehner, “Ephesians” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (Wheaton: Victor, 1983-c1985) 2:622.

[33] Jamieson, et al., A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, Eph 5:14; Blaikie, The Pulpit Commentary: Ephesians, 210.

[34] Bruce, The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians, 376; Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, Eph 5:14; Andrew T. Lincoln, Ephesians, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 42 (Dallas: Word, 2002), 332.

[35] Hoehner, “Ephesians,” 2: 639.

[36] Lincoln, Ephesians, 332; MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Eph 5:14.

[37] Wiersbe, The Bible Exposition Commentary, Eph 5:3.

[38] Jamieson, et al., A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, Eph 5:14.

[39] Blaikie, The Pulpit Commentary: Ephesians, 210.

[40] Robert G. Bratcher and Eugene Albert Nida, A Handbook on Paul’s Letters to the Colossians and to Philemon, Originally published under title: A Translator’s Handbook on Paul’s Letters to the Colossians and to Philemon., Helps for Translators; UBS Handbook Series (New York: United Bible Societies, 1993], c1977), 59.

[41] Carson, New Bible Commentary, Col 2:13; Norman L. Geisler, “Colossians” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (Wheaton, IL: Victor, 1983-c1985), 2:678; Peter T. O’Brien, Word Biblical Commentary: Colossians-Philemon, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 44 (Dallas: Word, 2002), 122; Edward R. Roustio, “Colossians” in the KJV Bible Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1994), 2461.

[42] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Col 2:13.

[43] Richard R. Melick, Philippians, Colossians, Philemon, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary, Vol. 32 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001, c1991), 262.

[44] Dunn, The Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; Carlisle: Paternoster, 1996), 163.

[45] Robert B. Hughes and J. Carl Laney, Tyndale Concise Bible Commentary, Rev. ed. of: New Bible Companion. 1990.; The Tyndale Reference Library (Wheaton: Tyndale House, 2001), 535.

[46] Chafer, “The Consummating Scripture on Security,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 107:426 (April 1950; 2002) 142; Jamieson, et al. (A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, Ro 8:10) rephrase Paul thus: “If Christ be in you by His indwelling Spirit, though your ‘bodies’ have to pass through the stage of ‘death’ in consequence of the first Adam’s ‘sin,’ your spirit is instinct with new and undying ‘life,’ brought in by the ‘righteousness’ of the second Adam”

[47] J. Barnby, The Pulpit Commentary: Romans, ed. H. D. M. Spence-Jones (Bellingham: Logos, 2004), 208; Dunn, Word Biblical Commentary: Romans 1-8, 431; Godet, Commentary on Romans, 304-05; MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Ro 8:10; Kroll, “Romans,” 2239.

[48] Even so, this is not to affirm that believers sin in the body but not in the spirit. The person sins; not parts of his being.

[49] The Letter to the Romans, ed. William Barclay, lecturer in the University of Glasgow, The Daily Study Bible Series, Rev. ed. (Philadelphia: Westminster, 2000, c1975), 105; Barnby, The Pulpit Commentary: Romans, 208; Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, Ro 8:10; Mounce, Romans, 179; Witmer, “Romans,” 2:470.

[50] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Ro 8:2.

[51] Mickelsen, The Wycliffe Bible Commentary: New Testament, Ro 8:5-13.

[52] Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, 816. “An oxymoron is a wise saying that seems foolish.”

[53] A. Duane Litfin, “1 Timothy” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (Wheaton: Victor, 1983-c1985), 2:742.

[54] Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, 818; Carson, New Bible Commentary, 1 Ti 5:6; A. C. Hervey, The Pulpit Commentary: 1 Timothy, ed. H. D. M. Spence-Jones (Bellingham: Logos, 2004), 96; Jamieson, et al., A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, 1 Ti 5:6; Homer A Kent, Jr. The Pastoral Epistles, Revised ed., (Chicago: Moody, 1958, 1982), 170; George W. Knight, The Pastoral Epistles: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids; Eerdmans; Carlisle, England: Paternoster, 1992), 219; Thomas D. Lea and Hayne P. Griffin, 1, 2 Timothy, Titus, electronic ed., The New American Commentary, Vol. 34 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001, c1992), 147; MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, 1 Ti 5:6; Mounce, Word Biblical Commentary: Pastoral Epistles, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 46 (Dallas: Word, 2002), 282.

[55] C. Sumner Wemp, “1 Timothy” in KJV Bible Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1994), 2503.

[56] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Re 3:1; Walvoord, “Revelation” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (Wheaton: Victor, 1983-c1985), 2:938.

[57] Alan F. Johnson, “Revelation” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 12 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1981), 449.

[58] Lenski, The Interpretation of St. John’s Revelation (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1943, 1963), 127.

[59]Charles L. Feinberg, “Revelation” in the KJV Bible Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1994), 2664.

[60] Mounce, The Book of Revelation, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1977), 110; Walvoord, The Revelation of Jesus Christ (Chicago: Moody, 1966), 79.

[61]G. K. Beale, The Book of Revelation: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids; Eerdmans; Carlisle, England: Paternoster, 1999), 273.

[62]David E. Aune, Word Biblical Commentary: Revelation 1-5:14, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 52A (Dallas: Word, 2002), 219.

[63] Ibid., 164; Woodrow M. Kroll, “Romans” in the KJV Bible Commentary, Edward E. Hindson and Woodrow M. Kroll general editors (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1994), 2235, states, “Sin has no existence apart from God’s law, since by definition sin is the violation of God’s law.” (bold his)

[64] Godet, Commentary on Romans, 274; Robert Jamieson, A. R. Fausset, and David Brown, A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, On spine: Critical and Explanatory Commentary, Romans 7:8 (Oak Harbor: Logos, 1997); Witmer, “Romans,” 2:466; The Nelson Study Bible: New King James Version, Earl D. Radmacher, general editor, H. Wayne House, New Testament editor, Romans 7:8, (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997); Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament, Romans 7:8; W.E. Vine, Romans 7:8 in Collected Writings of W.E. Vine (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1996); Horst Robert Balz and Gerhard Schneider, Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament, Translation of: Exegetisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament, 2 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990-c1993):461. A. Berkeley Mickelsen (The Wycliffe Bible Commentary: New Testament, Charles F. Pfeiffer and Everett F. Harrison, editors, Romans 7:7 [Chicago: Moody, 1962]) expresses a different understanding by saying, “Paul does not say that sin is not committed without law. He is saying that without law sin is not apparent to us. It takes a carpenter’s level to make clear how far from straight a board really is.”

[65] Murray, The Epistle to the Romans, 250.

[66] William MacDonald and Arthur Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Romans 7:8 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1995).

[67] Romans 7 describes Paul’s post-conversion struggle with his sin nature, not pre-conversion.

[68] Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, 538, 564.

[69] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Heb 6:1; B. F. Westcott, The Epistle to the Hebrews, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, n.d.), 144.

[70] Jamieson, et al., A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, Heb 6:1.

[71] Marvin R. Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament (Bellingham: Logos, 2002) 4:442.

[72] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Heb 9:14.

[73] Ibid. Heb 6:1.

[74] Zane C. Hodges, “Hebrews” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures, John F. Walvoord, Roy B. Zuck and Dallas Theological Seminary editors (Wheaton: Victor, 1983-c1985), 2:793.

[75] Hodges, “Hebrews,” 2:802. See also, Earl D. Radmacher and H. Wayne House, editors The Nelson Study Bible: New King James Version, Heb 9:14 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997).

[76] Bruce, The Epistle to the Hebrews, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964), 113; Paul Ellingworth and Eugene A. Nida, A Handbook on the Letter to the Hebrews, Originally published: Translator’s Handbook on the Letter to the Hebrews. c1983., UBS Handbook Series; Helps for Translators (New York: United Bible Societies, 1994], c1983), 110; James Freerkson, “Hebrews” in the KJV Bible Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1994), 2547; Jamieson, et al., A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, Heb 9:14; Leon Morris, “Hebrews” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 12 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1981), 53. Kent (The Epistles to the Hebrews, 106) sees the “dead works” as sins in general in 6: 1 but including “legalistic ceremonies which cannot impart life” in 9:14.

[77] Ellingworth, The Epistle to the Hebrews: A Commentary on the Greek Text, Spine title: Commentary on Hebrews (Grand Rapids; Eerdmans; Carlisle, England: Paternoster, 1993), 314.

[78] Ellingworth and Nida, A Handbook on the Letter to the Hebrews, 196.

[79] Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, 535. Hypallage is where two nouns are “reversed in order or construction without regard to the purely adjectival sense” of the clause. In this case “faith” and “dead” are interchanged and Bullinger (537) sees James actually meaning that “the man who says he has such faith is dead.”

[80] James Dunn (“Response to Michael P. Barber,” in Four Views on the Role of Works at the Final Judgment, Counterpoints, eds. Alan P. Stanley and Stanley N. Gundry (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2013) 201) describes “dead faith” as “not … true faith.” See also James Adamson, The Epistle of James, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976), 124; Jamieson, et al., A Commentary, Critical and Explanatory, on the Old and New Testaments, Jas 2:17; Simon J. Kistemacher, James and I-III John, New Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1986), 89-90, and “The Theological Message of James,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 29:1 (March 1986; 2002) 58; MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Jas 2:17; Ralph P. Martin, Word Biblical Commentary: James, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 48 (Dallas: Word, 2002), 85; Walter W. Wessel, The Wycliffe Bible Commentary: New Testament, Charles F. Pfeiffer and Everett F. Harrison, editors, Jas 2:15 (Chicago: Moody, 1962); John F. Walvoord, “Series in Christology, Part 4: The Preincarnate Son of God,” Bibliotheca Sara, 104:416 (October 1947; 2002) 423. Charles Ryrie, (Charles C. Ryrie, So Great Salvation (Victor, 1989), 133) says that “unproductive faith is a spurious faith.”

[81] J. Ronald Blue, “James” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures, John F. Walvoord, Roy B. Zuck editors (Wheaton, IL: Victor, 1983-c1985), 2:825; James Montgomery Boice, Christ’s Call to Discipleship (Chicago: Moody, 1986), 17; Peter Davids, Commentary on James, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 119; Hughes and Laney, Tyndale Concise Bible Commentary, 682; James D. Stevens, “James” in the KJV Bible Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997, c1994), 2590; Kurt A. Richardson, James, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary, Vol. 36 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2001, c1997), 133; Wiersbe, The Bible Exposition Commentary, Jas 2:14.

[82] MacDonald and Farstad, Believer’s Bible Commentary: Old and New Testaments, Jas 2:17. So, too say others: MacArthur, “Faith According to the Apostle James,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 33:1 (March 1990; 2002) 16, 22; Larry Richards and Lawrence O. Richards, The Teacher’s Commentary (Wheaton, Ill.: Victor, 1987), 1023; Robert L. Saucy, “Second Response to ‘Faith According to the Apostle James’ By John F. MacArthur, Jr.,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 33:1 (March 1990; 2002) 44.

[83] Barclay, The Letters of James and Peter, The Daily Study Bible Series, Revised edition, (Philadelphia: Westminster, 2000, c1976), 74; Chafer, “The Eternal Security of the Believer, Part 2,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 106:424 (October 1949; 2002) 401. Walvoord modifies Chafer’s position slightly and says that “while works are not the ground or justification for salvation, they can be the fruit or evidence of it” (“Christ’s Olivet Discourse on the End of the Age, Part VII: The Judgment of the Nations,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 129:516 [October 1972; 2002] 312).

[84] MacArthur, “Faith According to the Apostle James,” 32.

[85] As quoted by Wiersbe, The Bible Exposition Commentary, Jas 2:14.

[86] Aldrich, “Some Simple Difficulties of Salvation,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 111:442 (April 1954; 2002) 167; Davids, The Epistle of James: A Commentary on the Greek Text, 122, 134; William W. Howard, “Is Faith Enough to Save? Part 2,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 98:392 (October 1941; 2002) 500.

[87] John F. Hart, “How to Energize Our Faith: Reconsidering the Meaning of James 2:14-26,” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society, 12:1 (Spring 1999; 2002) 62-63.

[88] Paul Benware, “The Social Responsibility of the Church,” Grace Journal, 12:1 (Winter 1971; 2002) 7; Hodges, The Gospel Under Siege: Faith and Works in Tension, second ed. (Dallas: Redencion Viva, 1981, 1992), 30.

[89] Hodges, Absolutely Free: A Biblical Reply to Lordship Salvation (Grand Rapids: Academie, 1989), 125.

[90] Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, Jas 2:17.

[91] Hodges, The Epistle of James (Irving: Grace Evangelical Society, 1994), 63.

[92] Donald W. Burdick, “James” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 12 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1981), 183. He also fits into the first category when he says (182), “Faith that does not issue in regenerate actions is superficial and spurious.”

[93] Hart, “How to Energize Our Faith: Reconsidering the Meaning of James 2:14-26,” 48.

[94] J. Kevin Butcher, “A Critique of the Gospel According to Jesus,” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society, 2:1 (Spring 1989; 2002) 35. Hodges (“Calvinism Ex Cathedra: A Review of John H. Gerstner’s Wrongly Dividing the Word of Truth: A Critique of Dispensationalism,” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society, 4:2 [Autumn 1991; 2002], 65) correctly notes James’ figurative use of dead, but wrongly argues that this “implies that a dead faith was once alive, just as a dead body that has lost its spirit was once alive. He develops this analogy more fully in Absolutely Free [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1989], 125).

[95] Some might argue that James describes demons as having non-saving faith in James 2:19. Though James uses πιστεύω with demons, his use of “believe” is not a reference to either justifying or sanctifying faith. Rather, it refers to recognizing certain facts as true. James follows the verb with a ὅτι of content to describe what they believe, not in whom. When πιστεύωis used with regard to faith directed toward an object, the prepositions εἰςor ἐνare normally used with the object or person following, thus faith “in Jesus” or “in God.” Jesus employs both uses of πιστεύωin John 14:10-12 when He tells the disciples to believe what He has taught them, and then refers to someone believing in Him. Thus, demons are not trembling because God is the object of their faith, but because the undeniable truth about God terrifies them.