Introduction

This article complements an article that appeared in the Fall 2011 Dedicated Journal.[1] That article proposed an interpretation of Gal. 5:16-18 that promotes a more encouraging prospect for living a godly life than is often communicated in popular presentations. My purpose in revisiting this theme with a survey of Rom. 7:14-25 is that this passage, more than Gal. 5:16-18, has been used to throw considerable doubt on the believer’s chances to live a life freed from the domination of sin. This passage stands at the heart of this controversy; it is the crux interpretum for those desiring to understand Paul’s view of the power of the sinful nature in the heart of the believer.

Getting this passage right is critically important, especially for pastors and teachers whose goal is to “present everyone mature in Christ” (Col. 1:28). If Paul himself so struggled with sin that he despaired of being able to do what was right—a common interpretation of Rom. 7:14-25—then what chance does the not-so-motivated, weaker Christian have of doing what is right? A careful study will show that this passage should not be interpreted to mean that the believer is unable, despite the best intentions and will-power, to live a life of mastery over sin. Its message instead conveys much more hope.

Brevity demands clarity. Romans 7:14-25 has nothing to do with the struggle (It is a struggle!) of the believer to live a godly life. This passage does not address the sinful nature within the heart of a believer; it does not depict the conflicting desires within a Christian. This passage does not speak about sanctification; Paul is not writing about his present struggle with indwelling sin.[2] Rather, it concludes Paul’s teaching on how sin used the commands of the Law to secure unbelieving Jews in their sinful state and how the (Jewish) believer has been set free by the Spirit from sin and the Law to live a life characterized by righteousness. Paul has another purpose in mind that is very important to him: to defend the Law (really, to defend Paul himself) against the charge that it somehow is an ally of sin, that the Law itself is sinful.

This study supports the “unregenerate” view of Romans 7:14-25. This is the view that the struggle Paul describes in 7:14-25 is not that of a believer, but of an unbeliever. The struggle described is not that of just any unregenerate person, certainly not that of a Gentile. Specifically, it describes the struggle of a Torah-observant Jew to do what Yahweh has commanded him to do, but who finds it impossible to do. Is it then autobiographical? Does Paul allow his audience a glimpse into his own personal struggle with sin as a Pharisee before his conversion? This is possible, but not necessary. This could simply refer to Everyman Jew, given that Everyman Jew is Torah-observant, a lover of Torah who desires to please Yahweh by abiding by it. We should also leave open the option that in his powerful rhetoric declaring his failure to do what is right, Paul does some back-reading, describing his failure from the perspective of a converted Jew looking back on his pre-conversion days.

The title of this article suggests that contextual, thematic and literary concerns will be addressed in an effort to support the thesis stated above. If this passage is removed from its contexts, as it usually is in popular presentations, the struggle with sin sounds familiar—try as you might, you still sin. Who doesn’t have some “besetting sin” that seems to hang on despite our best efforts? For this reason this passage, when taken out of its context, continues to resonate with audiences. But audience response should not shape our hermeneutics. When remove passages from their contexts, misguided interpretations are almost inevitable. Such is the case here. Paul certainly deals with the believer’s struggle with indwelling sin, but not here in Romans 7:14-25.

These three elements—context, theme and literary devices—will be interweaved throughout this study since at times they overlap. As we think of the widest context for Paul’s remarks, we must begin with Paul himself at the time he wrote Romans and what has come to be called the “Jew-Gentile controversy.”

The Cultural/Theological Context: The Jew-Gentile Controversy

At the heart of the controversy was the relationship, if any, of Torah to the Gospel that Paul preached. The Jews assumed that Gentiles needed to come to God through the institution of Judaism. That had been the way God had operated for over 1400 years; why change now? Gentiles, very understandably, said, “No way are we going to be circumcised and live by the rules of the Law! Neither one is essential for our salvation.” Paul himself fueled the controversy because he evangelized the Gentiles as Gentiles, not as Jewish proselytes. To do that he believed and taught that the Law as a rule of life had come to an end for Jewish believers and believing Gentile proselytes to Judaism. The controversy became very personal for Paul when he was wrongly accused by the Jews of turning his back on his Jewish heritage, claiming that he had no more use for the Law of Moses, and that he actually advocated not living by it. Worst of all, they accused him of teaching that it did not matter if you lived a life of sin, because grace covers all sin!

Since Gentile conversions had become more prevalent than Jewish conversions, the issue could not be ignored. In fact, with so many Gentiles being saved and so few Jews becoming Christians, it appeared that a major shift in God’s plan of redemption for mankind was underway. This was extremely confusing to everyone—Gentiles as well as Jews. In the midst of this confusion, suspicion, and rumors Paul wrote Romans. Paul’s letter to the Romans, then, like all other New Testament epistles, is situational. While it rightfully can be called Paul’s treatise on salvation, that treatise is firmly set within the context of the Jew-Gentile controversy, at the center of which was the nature and function of Torah. A helpful way of reading Romans is to imagine in the background a group of frowning, hostile Jews, ready to jump on anything that Paul says that might be construed negatively toward Judaism in general, and Torah in particular. Now nearing the end of his ministry, Paul has often felt the sting of their opposition. He writes Romans with this group always in his mind, being careful at every opportunity to defend the Gospel and himself against charges of antinominianism and betrayal of Judaism and Torah.

Throughout the first five chapters, with the current controversy in mind, Paul cannot help but lay himself open to the accusation that he has adopted a negative attitude toward Torah. He has had to explain the Gospel vis-à-vis the Law, and in doing so has given the impression that somehow Torah has been linked with sin. Consider how the following statements could have been misinterpreted by this behind-the-scene group of Jewish antagonists who loved their religion and were completely dedicated to observing Torah. To obey Torah was to honor Yahweh; to speak against Torah was to blaspheme him.

- “for through the Law comes the knowledge of sin” (3:20a)

- “for the Law brings about wrath, but where there is no law, neither is there violation” (4:15)

- “but sin is not imputed when there is not law” (5:13b)

- “And when the Law came in that the transgression might increase” (5:20a)

Paul was not unaware of how his objectors would react to him repeatedly linking Torah with sin. He knew that at some point in his treatise he would have to explain more fully the relationship between sin, Torah and the Jewish unbeliever. This he does in Romans six through the first part of chapter eight.

The Thematic Context of Romans 6:1-8:17

We can now narrow down our study to the literary unit where 7:14-25 resides, beginning with chapter six and extending into the first half of chapter eight. The trigger that sets off the exclamation in 6:1, “What shall we say then? . . . By no means!” is Paul’s climactic conclusion to the Adam-Christ contrast of Rom. 5:12-21. With a dramatic flourish, Paul extols the grace of God in saving sinners, both Jew and Gentile. But he does so with an apparent knock against Torah: “Now the law came in to increase the trespass, but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more” (5:21). Paul’s adversaries now have all the evidence they need to confirm their suspicions about Paul! Did not Paul just say that it does not matter what sins a person commits (“sins”=laws of Torah disobeyed), grace covers them all? So why not live a dissolute life in violation of Torah? Paul spends two and a half chapters to debunk this notion, explaining how that his Gospel has set the Jew free not only from sin but also, necessarily, from the Law. In so doing, he will make sure that his audience understands that he has never been opposed to the Law. He will explain that the Law’s main problem was that it could only command; it was powerless to produce a godly life. It condemned the sinner; it could not justify the sinner. That was the role of the Spirit through the Gospel.

As mentioned at the outset, one of the mistakes made in interpreting chapter seven is lifting it out of this thematic context. Throughout this section Paul employs a number of thematic contrasts to explain what happens when a Torah-observant Jew believes the Gospel and is saved: old man/new man; bondage/freedom; Law/Spirit; death/life. The nature of these contrasts is important to note. They do not describe the difference between an obedient Christian and a disobedient Christian; they describe the difference between the unsaved (Jews primarily) and the saved. The following chart highlights the contrasting themes that are central to these chapters.

Contrasting Themes in Romans 6:1-8:17

| The Realm of Law and Sin(unsaved) | The Realm of the Spirit and Righteousness(saved) |

Old Manê Alive to sin and dead to God ê A slave to sin and free from righteousness ê Death |

New Manê Dead to sin and alive to God ê Free from sin and a slave to righteousness ê Eternal Life |

These contrasting themes are very important to recognize. They set the theological background needed to interpret properly any text within these two-and-a-half chapters. As the chart indicates, Paul has not left the general subject of justification (chapters 1-5) to now deal with sanctification. He is still dealing with the subject of justification, now taking the time in these chapters to apply the doctrine in a way that addresses concerns regularly expressed in the ongoing Jew-Gentile controversy.

The larger thematic context of our passage narrows its focus in the specific literary unit that comprises Romans six and seven. While these two chapters remain connected thematically to the first part of chapter eight, they more tightly connect to each other than to chapter eight.

The Literary Unity of Romans 6 and 7

Paul structures Romans 6-7 by means of one of his favorite literary devices, the rhetorical “What then? May it never be!” or its equivalent. This occurs in the four stages of his argument: 6:1; 6:15; 7:7; 7:13. They serve as subject headings and thus indicate the flow of Paul’s argument throughout these chapters.

6:1 What shall we say then? Are we to continue in sin that grace might increase? May it never be!

Inconceivable! Once you die, that is it; no more of that life. We have become new people because of our union with Christ. We died to sin and now we live for the glory of God. So act like the dead (to sin) and the resurrected (to a new life of righteousness) people that you are!

6:15 What then? Shall we sin because we are not under law but under grace? May it never be!

No, the change from living under the Law of Moses to this age of unparalleled grace in Christ provides no basis for a life of sin. Just the opposite is the case. Our life now in this age of “grace” is characterized by righteousness. It is completely different than when we Jews were under the Law. Then we were slaves to sin; now we are slaves to righteousness.

This section begins with the question, “What then? Shall we sin because we are not under the Law but under grace?” One would think that the answer, which immediately follows, would say something about the Law of Moses. But Paul does not mention the Law again through the end of chapter six. We must ignore the chapter break in our Bibles; the section carries on into chapter seven, which does deal with the Law.

Paul’s illustration of the married couple in 7:1-6 is one of those illustrations that you don’t want to press too far. Neither the husband nor the wife represents the believer, yet in a way both do. The point is that Jews who have come to embrace Christ have died to both sin and also to the Law and now are freed to live a righteous life for the first time in their experience.

7:7 What shall we say then? Is the Law sin? May it never be!

The Law was in no way responsible for the spiritual death of those under it. The only reason that “Law” and “sin” can be thought of together as resulting in spiritual death is that Law made the Jews aware of what sin was. It defined sin. It created new categories of sin. It made it possible to sin in ways that nobody had sinned before. Unfortunately, however, it did nothing to remedy sin, so Jews died in their sin.

Romans 7:7 begins a defense of the Law that will be set forth in two complementary sections, the second being 7:13-25. In 7:7-12 Paul says that the Law cannot be sin, because it reveals the will of God; it tells us (Jews) what is right and what is wrong. He then explains that sin is the real culprit, not the Law. Sin took advantage of the fact that the Law could only command; it could not enable the unsaved Jew to obey it.

7:13 Therefore did that which is good become a cause of death for me? May it never be!

No, the Law did a good thing. The Law showed me the right way to go. But without the life that the grace of God provides, I am completely helpless to obey it. Try as I might I cannot do anything right, anything at all that pleases God. I am a slave to sin. So it is sin, and only sin, that kills, not the Law. The only remedy for this is the freedom from sin and death that the Spirit makes possible.

Romans 7:13-25 restates the thought of 7:7-12, only in more detail and with stronger rhetoric. Paul has to convince his Jewish listeners that he really means it when he says that the Law is not to blame for the present lost condition of the Jews. So 7:13-25 is a very dramatic and persuasive depiction of the process itself, one that should convince Jews that indeed the Law, while not the direct cause of Jews being enslaved in sin and subject to death, was nevertheless the means by which sin enslaved the Jews.

The key to this interpretation of 7:14-25 is to see that the rhetorical question of v. 13 introduces it. The question of v. 13—“Did that which was good [Torah] bring death to me?”—is answered with vv. 14-25. Perhaps one reason for confusion can be credited to our translations. The NASB, for example, inserts a paragraph break between v. 13 and v. 14 with “The Conflict of the Two Natures” at the head of v. 14. The NLT does the same: “Struggling with Sin” heads v. 14. If, however, v. 13 is allowed to stand at the head of this section, in the same way that the three other headings do, then it is readily apparent that the topic of vv. 14-25 is how the Law of Moses related to the spiritual death of the Jews, not the believer’s struggle with the sinful nature.

As the investigation of this passage narrows, focus shifts finally to the passage itself, 7:14-25. Because it has its own distinctive literary quality, it deserves separate attention.

The Cyclical Structure of Romans 7:14-25[3]

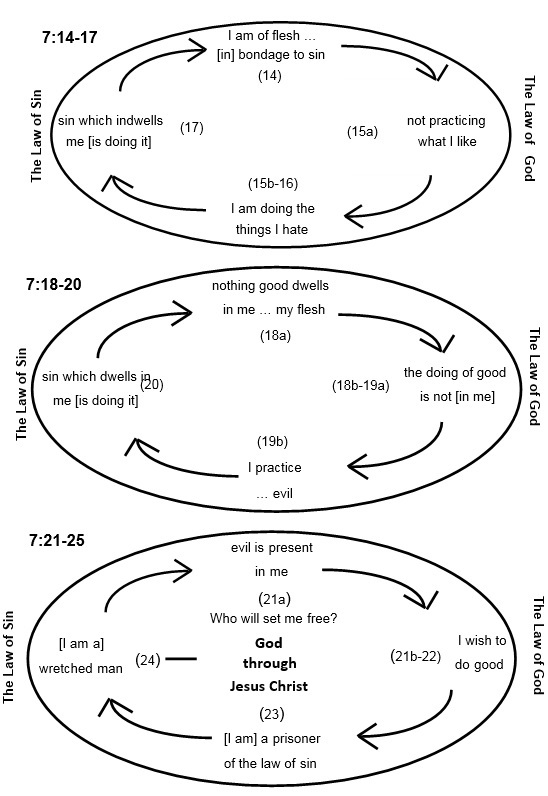

Willsey has observed that Rom. 7:14-25 consists of three confessional cycles, four sections to each cycle.1 Seifrid has noticed the same basic structure.[4] Seifrid understands the passage to be an example of Jewish penitential language, which “invites the reader to the same confession.”[5] Unlike Willsey who sees four sections to each cycle, Seifrid sees three. “The passage should be seen as consisting in three sections, each beginning with a statement of self-knowledge, moving to a narration of behavior and ending with a diagnosis of the egō (“I”) confirming the confession which began the section.”[6] It should be noted that the cyclical structure itself does not support the unregenerate interpretation of this passage, nor does it support the regenerate view. It rather explains why the passage sounds so repetitive; it is designed to be! The repetition of the cycle is a dramatic rhetorical touch by Paul. If it is worth saying once, it is worth saying three times to hammer home the point—total helplessness of the “I” portrayed here. The three sections are vv. 14-17, vv. 18-20, and vv. 21-25.

The “I” and the present tense are the most serious problem facing the unregenerate view. However, they can be explained as Paul’s dramatic way of including his Jewish audience in his argument, or as Seifrid puts it, Paul “invites the reader to the same confession.”

As has been noted, this passage repeats the basic thought expressed in 7:7-12. In that passage, there is no question that Paul is talking about his pre-conversion experience with Torah. He refers to the past, apparently to a time of his childhood or youth in which he came to realize that the Law could only command; it did not provide the power to obey.

If it is objected that according to Paul’s own testimony the sinner does not seek after God or desire to do his will (3:10-18), we must keep in mind that is writing “to those who know the law” (7:1) and desire to live by it. Paul’s description of this desire would not be applicable to a pagan Gentile or a non-practicing, Hellenized Jew; it would be, however, to someone like Paul the Pharisee and his Torah-devoted antagonists.

In each of the three cycles Paul admits to complete inability to do what is right. Not once does he do a single thing that is pleasing to God. While the believer may at times feel this way, this does not accurately describe the struggle to do what is right. At least some of the time the believer does what is right! Or at least it is possible to do what is right. Here it is not only total failure, it is total inability.

The first part of v. 25, “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!” is obviously not the cry of an unsaved Jew. As he rounds out his third cycle of desire and failure, and before he completes it, Paul cannot help himself but to shout out this praise to God for his saving grace. This statement, then, should be viewed as a parenthesis. He will develop this thought with the first part of chapter eight, but he first must finish the third cycle. This he does in the second half of v. 25 with a summary statement of the whole process that he has been describing since v. 14: “So then, I myself serve the law of God with my mind, but with my flesh I serve the law of sin.”

In conclusion, to summarize Paul in Romans 6 and 7: “We Christians cannot think to live sinful lives for the simple reason that the old life in sin is forever gone; a new life pleasing to God has taken its place. We are now happy slaves to righteousness whereas before we were slaves to sin and dead spiritually. The change from the age of the Law to the age of Spirit has made this possible. That’s because the Law only killed, whereas the Spirit gives life. Please don’t misunderstand me! I’m not suggesting that the Law itself was in any way evil, or that the Law itself killed anybody. Sin took advantage of the fact that the Law could only condemn us and not save us. Sin used the Law as an unwitting partner in damning us Jews to hell. It was sin, not the Law that killed. Because of the Spirit’s life-giving ministry, however, all this is changed. We can now live a life of righteousness, gladly doing the will of God, and no longer under the domination and condemnation of sin.” [Amen!]

[1] See article at https://blogs.corban.edu/ministry/index.php/2011/10/spirit-powered-living-a-positive-interpretation-of-galatians-516-18/

[2] Paul’s series of “I” statements will be addressed later in this article.

[3] Jack K. Willsey, “A Textbook for the Study of Romans” (D. Min. diss., Western Conservative Baptist Seminary, 1989), 200-01.

[4] Mark A. Siefrid, “The Subject of Rom 7:13-25.” Novum Testamentum 34 (October 1992), 327.

[5] Ibid., 326.

[6] Ibid.

Thank you for the careful and articulate analysis. I am deeply interested in how your insights might be further supported by the first sentence of chapter 8. For instance, does the time/spatial indicator often translated “now” as in “therefore there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” continue the persuasive force of your position? Again, thank you for taking the time to study and to present your analysis creatively and clearly.